EU CBAM + ETS: the 2026 handover from “free protection” to border pricing

Author: Justin Kew

Geopolitics now shaping carbon enforcement

January 2026 is the inflection point. CBAM moves into its payment reality, while the EU begins the multi-year removal of ETS free allowances for CBAM sectors, completing the structural transition from “internal protection” to “border price transmission”. The policy intent is simple: if EU producers must pay for carbon, imports should face an equivalent constraint.

This week’s Commission communications and Brussels policy commentary reinforce that the EU is not backing away from CBAM. It is making it more enforceable and more politically durable: less admin burden for low-volume importers, tighter anti-circumvention, and a clearer line of sight to expansion and exporter treatment.

What changed (and why it matters now)

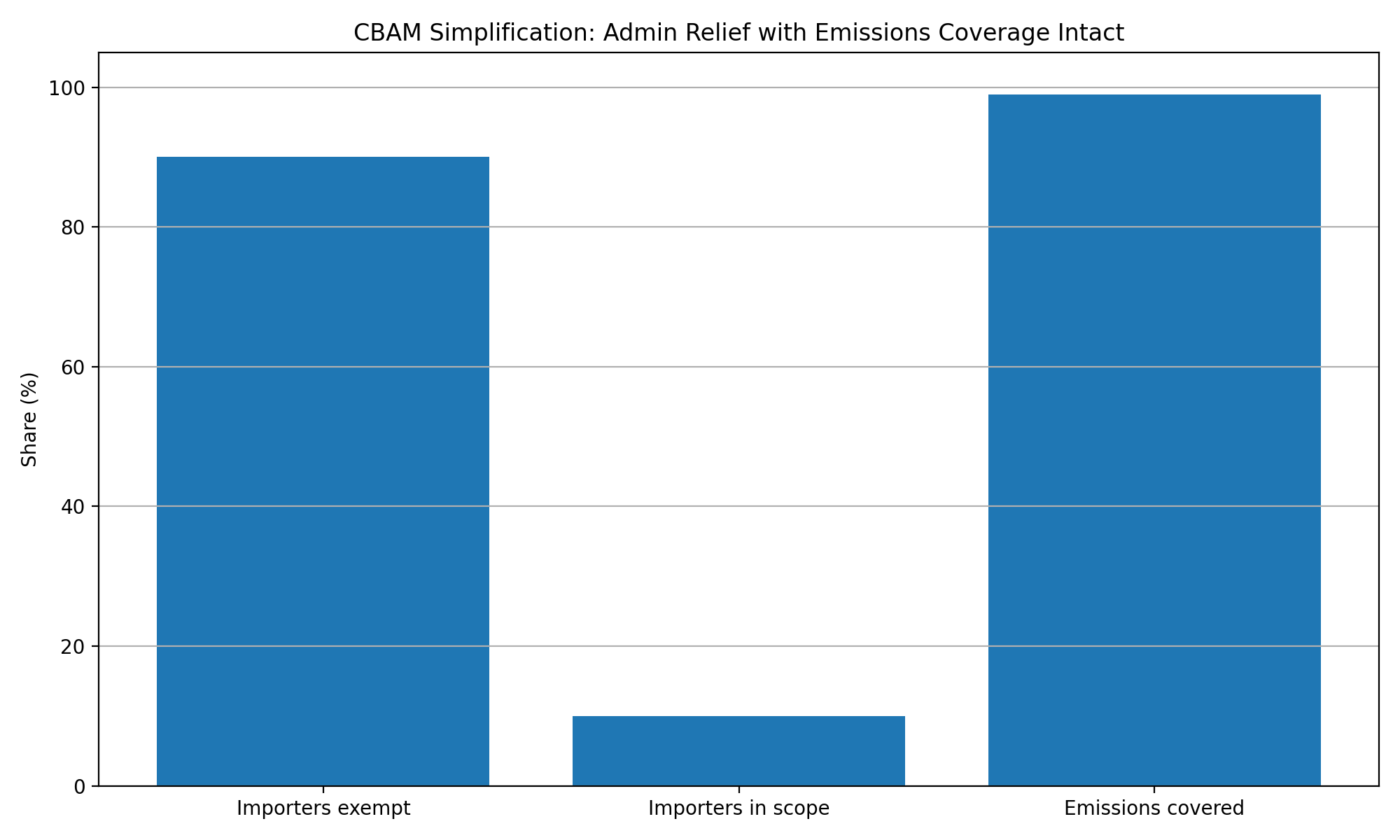

CBAM simplification is now formal EU policy, not a rumour. Council has signed off a simplification package that introduces a 50-tonnes-per-importer-per-year de minimis threshold, exempting the vast majority of smaller importers while retaining coverage of the overwhelming majority of embedded emissions.

That simplification is paired with a second message: enforcement and loopholes are the priority. The Commission has explicitly framed its recent proposals as “closing loopholes” and “strengthening efficacy”, including a push toward downstream coverage and anti-circumvention measures ahead of the 2026 phase.

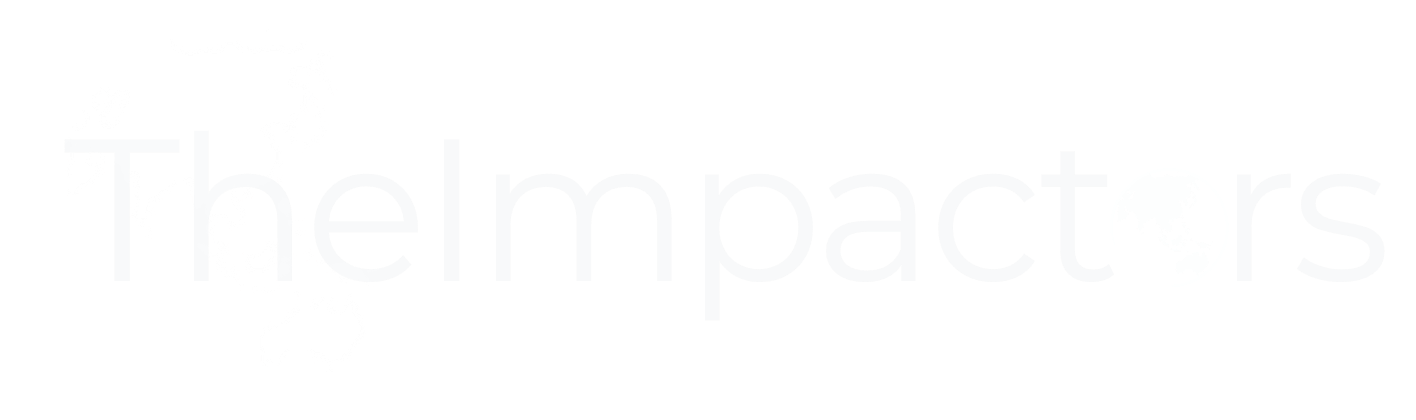

The ETS free-allowance phase-out is locked in

The EU is not keeping free allowances as a long-term competitiveness buffer for CBAM sectors. The phase-out schedule is defined and publicly stated, running 2026 to 2034, with CBAM phasing in at the same pace.

This is the critical economic point: Europe is replacing “free carbon” with “border carbon”. If you model industrial margins, you should treat that as a permanent regime shift.

The export problem

A central critique in European policy circles is the “export exposure” problem: CBAM equalises carbon costs for imports, but it does not automatically protect EU producers when they export into markets without comparable carbon pricing. This is now an active policy debate and is being analysed explicitly in European research, including work on whether a WTO-compatible approach could be designed.

Investors should translate this into a practical outlook: expect further policy engineering—not because CBAM is failing, but because the EU is trying to make the regime durable across a decade of trade pressure.

Implications for emerging-market producers: margin compression becomes structural

For emerging-market exporters, CBAM increasingly behaves like a performance filter rather than a simple tax. Producers with carbon-intensive production processes face a structural headwind when selling into the EU, particularly where buyers cannot fully pass through costs.

Most exposed sectors (today’s CBAM scope):

Steel: blast-furnace intensity vs EAF economics becomes a trade variable

Cement: high intensity + limited short-term abatement options makes exposure acute

Aluminium: power mix determines competitiveness

Fertilisers: gas and process emissions become border-priced

As the EU tightens enforcement, two practical realities become decisive:

Verified, installation-level emissions data is no longer a “nice to have”; weak data can force penalising default values.

Procurement shifts: EU buyers begin treating embedded emissions as a supplier selection criterion, not a reporting line item.

The supply-chain effect: compliance becomes commercialised

The simplification regime does not remove pressure. It concentrates it. The EU is exempting many small importers administratively, but it is making sure the policy still captures almost all emissions in covered sectors—meaning the compliance burden shifts toward the material flows, and therefore toward the major EU importers and their upstream suppliers.

That is where the supply chain reprice happens: contracts, data requirements, verification, and price adjustments increasingly move upstream—especially into Asia and other emerging markets.

Geopolitics is now part of CBAM design, not a side issue

CBAM is increasingly industrial policy infrastructure under geopolitical stress. The EU is operating in a context of trade fragmentation, energy-security policy, and strategic autonomy. The Commission’s emphasis on loopholes, downstream scope, and enforceability is consistent with a bloc that is less willing to tolerate strategic dependencies being underwritten by “cheaper, dirtier” imports.

Conclusion

From January 2026, carbon pricing becomes trade pricing. The ETS free-allowance phase-out and CBAM ramp-up represent a single handover: away from internal protection and toward border equalisation. The policy direction is not weakening; it is being operationalised—simplifying the admin perimeter while hardening enforcement on material flows.

For emerging-market producers in steel, cement, aluminium and fertilisers, the question is not whether CBAM “happens”. It is whether they can compete on verified carbon intensity in a world where geopolitics is increasingly shaping market access.

References: