Europe’s Auto Reset: Policy Hesitation vs China’s Execution

Author: Justin Kew, Martin Sacchi

The EU Commission put forward the EU Automotive Package on the 16th Dec 2025. Europe’s automotive industry has become a live case study in how geopolitics, industrial policy and execution discipline now determine competitive outcomes. The European Commission’s automotive competitiveness package was already a signal that the EV transition is no longer just a climate exercise. Germany’s recent intervention to soften or effectively halt the trajectory of the internal combustion engine (ICE) ban has sharpened that message further.

What is emerging is not a rejection of decarbonisation, but a loss of policy coherence at precisely the moment when competitors are accelerating with clarity. The contrast with China could not be starker — and the results are now visible in technology leadership, cost structures and global market share.

The EU automotive package: flexibility as damage control

The Commission’s automotive package is built around pragmatism. It aims to preserve industrial capacity while maintaining long-term climate objectives, focusing on three areas: greater flexibility around CO₂ compliance pathways, demand support via corporate fleets, and accelerated investment in batteries, recycling and upstream resilience.

Germany’s role has been pivotal. Berlin has pushed hard for exemptions and flexibility around the 2035 ICE phase-out, particularly through the recognition of e-fuels and a softer interpretation of intermediate targets. Politically, this reflects domestic pressure to protect incumbents and employment. Economically, it acknowledges that the pace of transition has outstripped Europe’s industrial readiness.

For investors, the signal is mixed. Flexibility reduces near-term margin pressure on OEMs, but it undermines long-term certainty — precisely the ingredient required to justify capital-intensive investments in batteries, charging infrastructure and materials processing.

Germany’s ICE pause: what it really signals

Germany’s effective braking of the ICE ban on the same day is not about technology neutrality; it is about industrial defensiveness. Europe’s largest auto market and manufacturing base is buying time.

However, time bought without execution has consequences. Delaying the transition does not slow global competition; it simply shifts learning curves and cost reductions elsewhere. By weakening the inevitability of the EV pathway, Europe risks discouraging precisely the scale investment required to close the gap with global leaders.

This is the central paradox: flexibility intended to protect industry may, over time, entrench its disadvantage.

China: no policy backtracking, only execution

China’s approach has been fundamentally different. There has been no equivalent policy reversal, no public debate about delaying electrification targets, and no attempt to preserve ICE incumbency as a strategic objective.

Instead, China has treated EVs as a national industrial priority, executing consistently across four dimensions:

Technology evolution: Chinese OEMs have moved rapidly up the value chain, integrating advanced software, vehicle operating systems, battery management and driver-assistance features. Product cycles are faster and iteration continuous.

Battery leadership: Scale deployment of LFP batteries, rapid commercialisation of sodium-ion technology, and dominance in cell manufacturing have driven cost curves down decisively.

Charging infrastructure: China has built the world’s densest charging network, including ultra-fast corridors, removing adoption friction and enabling mass-market uptake.

Supply-chain control: From materials processing to power electronics and motors, China’s vertically integrated supply chains reduce bottlenecks and enable rapid scaling.

Crucially, this strategy has not wavered in response to short-term market stress. Loss-making phases were tolerated to build scale, learning and cost leadership.

The results: EU hesitation vs China momentum

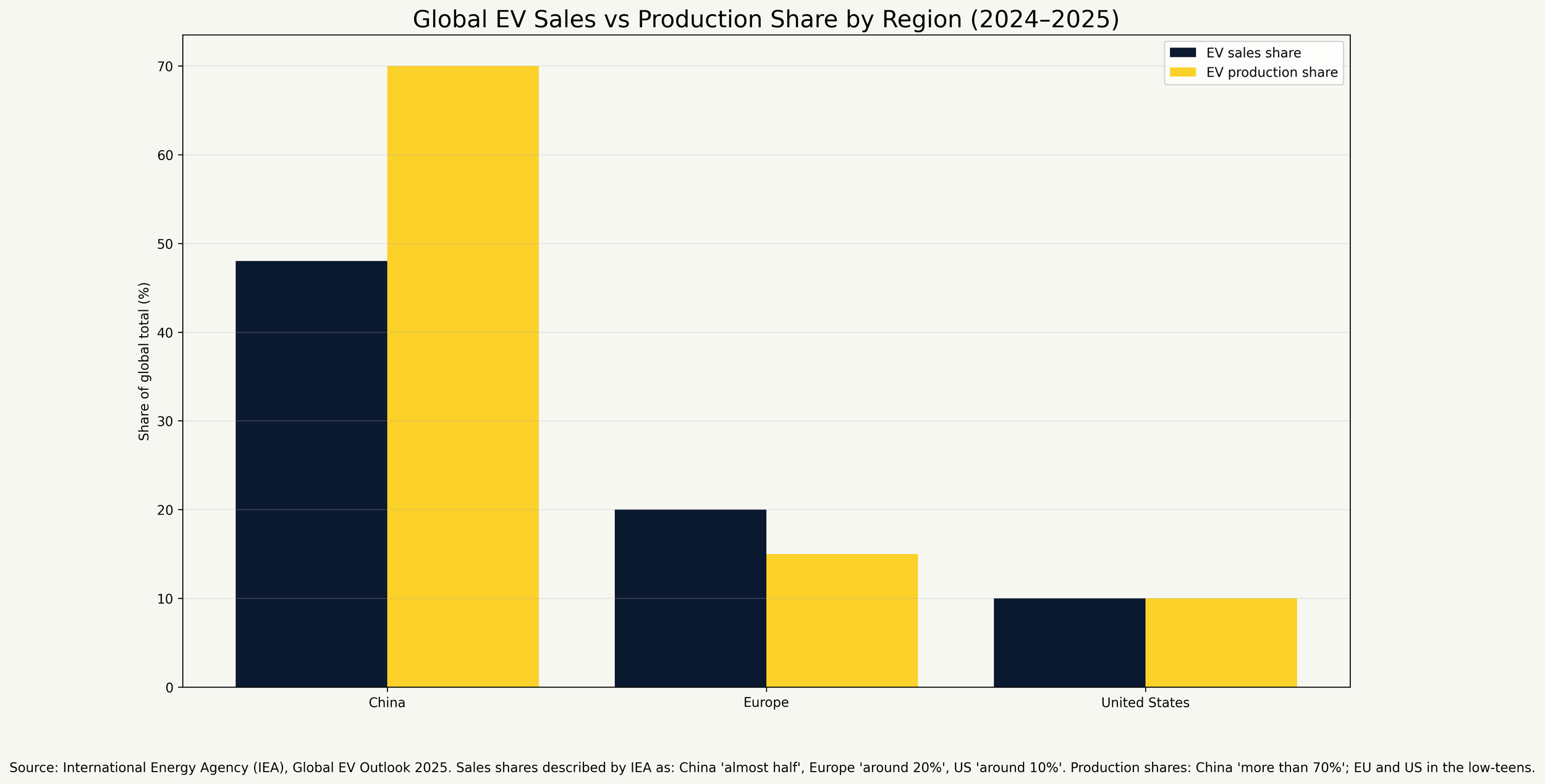

The divergence in outcomes is now measurable.

China accounts for around half of global EV sales and over 70% of global production, and Chinese manufacturers are increasingly competitive on quality, not just price. Exports and overseas assembly are driving rapid penetration into Europe, Southeast Asia, Latin America and the Middle East.

Europe, by contrast, faces:

slower EV adoption,

higher vehicle and battery costs,

fragmented charging infrastructure,

technology both user experience and drive train,

and dependence on external supply chains for materials and processing.

Germany’s ICE pause may stabilise domestic OEMs in the short term, but it does nothing to address these structural gaps. Indeed, by blurring the direction of travel, it risks widening them.

The United States: different tools, similar tension

The US has avoided overt backtracking but faces similar economic pressures. Its response has been to hardwire policy through subsidies and exclusion rules rather than mandates. However, recent corporate pivots — notably Ford’s decision to scale back large EV investments and refocus on smaller EVs and hybrids just announced this week — underline the same reality: EV economics remain challenging without scale, cost leadership and supply-chain depth.

Unlike Europe, the US has chosen enforcement over flexibility. Unlike China, it still lacks integrated supply chains.

What this means for investors

The automotive transition is no longer a debate about emissions targets. It is a contest between execution models.

Europe is recalibrating but risks confusing flexibility with strategy.

Germany’s ICE intervention signals industrial anxiety rather than competitive confidence.

China is compounding advantages through relentless execution.

The US is using policy architecture to compensate for structural gaps.

For investors, the implication is clear: policy certainty and ecosystem depth matter more than stated ambition. Markets are now rewarding those who can scale technology, infrastructure and supply chains — and penalising those who hesitate.

Conclusion

Germany’s effective halt to the ICE ban crystallises Europe’s dilemma. Flexibility may ease near-term pressure, but it does not substitute for industrial execution. In a world where China continues to push forward without policy reversals, hesitation has a cost.

The divergence between Europe and China is no longer theoretical; it is visible in technology maturity, charging infrastructure, supply-chain resilience and global market penetration. For investors, autos have become a geopolitical industry, where outcomes are determined less by regulation alone and more by the consistency, credibility and speed with which policy is turned into industrial reality.

Understanding that distinction is now essential — because in this cycle, delay is not neutrality, it is disadvantage.